By Glen Paul Hammond

“All is vanity.” – Ecclesiastes 1:5

Ernest Hemingway’s work is rooted in the struggle of existence, in what Kierkegaard was said to describe “as the struggle of the living being against non-being” (May 19). In the meaningless universe of the Old Testament’s Ecclesiastes, where generations replace generations in an endless cycle, even the search for meaning ends with an assertion that for the individual it must come from within, generated by an organism who creates his own values. This is the Hemingway Hero: A man not victimized by the vicissitudes of life, but one who acts upon what life throws at him—an individual who, through an act of will, provides form to chaos; one who acknowledges that the harsh truths of life necessitate the preparedness to cope with its realities and, as a result, accepts the responsibility, as Jake Barnes does in Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises, to act well rather than to act badly. Hemingway’s protagonists are made heroic by a code of conduct that allows the individual to combat futility with dignity, a dignity derived from the self-control necessary to utilize the values that the hero himself has generated. In one of Ernest Hemingway’s most famous short stories, Fifty-Grand, an illustration of such heroism is provided by its protagonist, the boxer Jack Brennan.

Early on in the author’s classic 1927 story, Hemingway reveals the three main priorities in the life of Jack Brennan: money, family and boxing. At the moment of meeting Hemingway’s hero, he is at a health camp preparing for his very last fight. The training has not been going well and it seems likely that he will lose the title he currently holds to an up and coming fighter named Walcott who, Jack says, “wants the title bad” (Hemingway 241). One of the problems Jack is having is insomnia and when asked by his constant companion in the story, Jerry, what keeps him up at night, he reveals the three main preoccupations of his life:

“Oh, I worry,” Jack says. “I worry about property I got up in the Bronx. I worry about property I got in Florida. I worry about the kids. I worry about the wife. Sometimes I think about fights” (Hemingway 234).

This tidy paragraph provides all the insight needed to understand the motivations of Jack Brennan. He is concerned about his assets, his family, and his professional bouts. This is important since it sets the reader up to recognize what Hemingway really wants to highlight. Namely, an illustration of the way his protagonist successfully pulls all these parts of his life together through a value system that allows him to achieve each goal and, in turn, provide a sense of meaning to his life.

In this endeavor, one of the essential characteristics of Jack Brennan’s code of conduct is self-discipline. According to the story’s narrator, Jack is a versatile fighter who can work the ring as both a classic boxer as well as a brawler. Yet, for all his motivation to perform at the very highest levels of his profession, Hemingway’s protagonist gives no indication that boxing is a passion; rather, for Jack Brennan, it is simply a means to an end. At one point, he wistfully acknowledges that he has sacrificed much in order to box and this is where Jack’s self-discipline is highlighted. Since, his ultimate career concern is to acquire as much money as he can, anything that impedes this must be discarded. At one point, the story reveals that one of Jack’s favorite pastimes had been gambling on horses. However, when asked why he gave it up, the boxer simply responds that he “lost money” doing it (Hemingway 233). Being careful with how he spends his money on a daily basis is also a manifestation of how his self-discipline maintains his monetary goals. Along with being frugal with tips, readers are informed that Jack resists calling his wife long distance and, instead, uses the post to keep in contact with her, since, as one character in the story puts it, “A letter only costs two cents” (Hemingway 234). Doing what it takes to earn and save money is not his only sacrifice. Another of Jack’s favorite pastimes was drinking. Jack tells his friend Jerry, “I like liquor pretty well. If I hadn’t been boxing I would have drunk quite a lot” (Hemingway 239). Temperance is part of his training and training is an essential component in his quest to achieve success in the ring. It is this part of his life that requires the greatest sacrifice.

By having Jack repeatedly mention his family, Hemingway emphasizes over and over that Jack Brennan is a family man who finds meaning in his role as both husband and father; yet, due to his profession, much of his life has been spent away from home. For Jack, time spent at training camp is measured in the amount of time it takes him away from his wife and kids. “You ain’t got any idea how I miss the wife,” he tells his friend Jerry. You ain’t got any idea. You can’t have an idea what it’s like” (Hemingway 239). And, while “Being away from home so much,” is articulated by Jack as one of the major regrets in a life dedicated to boxing, it also provides for the story’s greatest illustration of the role self-discipline plays in the accomplishment of his and, therefore, every man’s life goals. When Jerry suggests that Jack solve his problem of being isolated from his wife for so long by having her come out to the training camp, he refuses. She would distract him from his training and, alluding to the sportsman’s practice of abstaining from sexual intercourse as a way to enhance athletic performance, he adds that he is “too old for that” (Hemingway 234). His observation concerning his age brings up another important feature that a Hemingway Hero consistently demonstrates, the honesty to confront and accept the truth about oneself.

The real world demands an understanding of one’s actual position in it and, so, self-awareness is an essential tool in the negotiation of it. Along with hiring his manager to maintain the brand “Jack Brennan, Champion Boxer,” with the press—since, as Jack confesses, he is too “dumb” to do it himself—Hemingway’s hero also self-regulates. At one point, suspecting that his training is not going well, he seeks verification of this suspicion by asking his friend Jerry, “What do you think about the shape I’m in?” When Jerry tries to avoid responding by giving him an answer he thinks Jack would prefer, the boxer insists on hearing the truth. “Don’t stall me,” he tells Jerry, forcing him to respond honestly and admit, “You’re not right” (Hemingway 234). This verification of his condition turns out to be a very important piece of information, since it gives Jack the necessary motivation he will later need to make a vital career choice.

Midway through the story, Jack is approached by two professional gamblers, Morgan and Steinfelt, with an offer to make more money on the fight by throwing it and the boxer accepts. “How can I beat him?” Jack asks Jerry, after admitting he bet fifty-grand on his opponent. “I got to take a beating. Why shouldn’t I make money on it?” (Hemingway 240). It is important to note, that while Jack acknowledges he does not feel good about the arrangement he has made, he does not consider it immoral; this is because the Hemingway Hero does not simply adopt the moral attitudes of his society, but rather operates by his own set of self-generated principles. Jack is in boxing for the money and, on the eve of his last fight, he can make more by intentionally losing it; as a result, he holds true to his main objective in choosing his profession in the first place. Understanding this illustrates just how essential self-awareness has been in the ultimate success of Jack Brennan.

Readers are informed that Jack Brennan’s quest for money is rooted in his desire to create the best life he can for his children. However, even though his money gets his daughters into a high-end school, the way he gets the money does not give them the kind of social status that he would like them to have with the other “society” children. “’Who’s your old man?’” he tells Jerry, mimicking the kind of harassment his daughters get subjected to, ‘My old man’s Jack Brennan,’” and then to emphasize his point, he adds, “That don’t do them any good” (Hemingway 239). So, the question is, why did Jack choose boxing as opposed to some other more high-status profession? Since Jack himself remarked earlier in the story that he recognized his own lack of intelligence and Jerry informs readers later that, “There wasn’t anybody ever boxed better than Jack,” the answer seems obvious: Boxing is his natural gift and, accepting this, he worked toward his strengths when choosing what he would do to make a living for his family. To do otherwise would undoubtedly have led to either a less satisfactory result or failure.

As stated above, Jack has three main priorities in life, yet, Hemingway makes it obvious that they are prioritized in a particular order. For Jack Brennan, boxing is a means to acquire the money necessary to best serve the interests of his family, which is the ultimate goal. While he has the natural ability to be a boxer, overall success is dependent on him acquiring the knowledge and skill required to outperform other talented prizefighters. Yet, even these characteristics would not be sufficient if Jack did not have the courage to step into the ring in the first place. This, therefore, highlights another of the ingredients necessary in the quest for the author’s ideal representation of manhood and, therefore, meaning.

The hallmark trait of any Hemingway Hero—courage.

In a world that operates at random, hurling what Shakespeare’s Hamlet calls “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” at each of us, courage is an act of will (Shakespeare 3.1.58). It is what the psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger articulated in his more fully developed view of Freud’s theory of man, when he stated that becoming a man is rooted in a being that “looks its own and mankind’s fate in the face, a being that is steadfast…one taking its own stance, or one standing on its own feet” (May 31). Though he knows death is inevitable and the forces of life determine much of his fate, he does not live his life as a “living-dying” being, beaten about by what the world throws at him, rather, through acknowledging and accepting all that he cannot control, he accepts responsibility for and embraces all that he can control and, as Binswanger puts it, forges out that part of his life with the hardened hammer of his own will (May 31).

This is the main thrust behind the kind of heroism that Hemingway champions and Jack Brennan demonstrates this, as any bullfighter does on any given Sunday afternoon, whenever he steps into the ring. Throughout Fifty-Grand, Hemingway makes it clear that the upcoming fight will be a terrible ordeal. Jack Brennan is at the very end of his career and the young opponent he is about to face is now the kind of fighter that he once was but can never be again. Yet, to achieve his goal, he must face him anyway. From the earliest reference to the event, it seems clear to everyone that Brennan will not only suffer a defeat, but that the aged boxer will also have to pay a great physical price in the final confrontation of his career. The owner of the health farm, Danny Hogan, says that Brennan’s opponent, will “kill him…. He’ll tear him in two” (Hemingway 234). Jack realizes this also and, as a result, books a room at a local hotel for the night of the fight. Regarding this, Jerry states, “I thought he must be figuring on taking an awful beating if he doesn’t want to go home afterward” (Hemingway 234). Thus, the two sides of Brennan’s fate articulates the entire challenge of man. The now unbeatable natural force that Brennan must face, the younger fighter Walcott, is the personification of those life forces that, in the end, will determine a man’s fate; yet, the decision to step into the ring and to confront it, is that side of the equation where a man exerts his own will and, in so doing, determines that part of his fate that can be determined. This is, for Binswanger, the only way a man can be a man and avoid becoming a victim: “Only the two sides together can take in the full problem of sanity and insanity” (May 31). For Ernest Hemingway, this takes courage.

However, before the story’s end, there is one final element that the author makes sure to highlight as an essential part of man’s nexus to the path of meaning—poise and endurance. Brennan will lose the fight and he will do so willingly but, the protagonist points out that he will go out on his own terms, and, for him, this means not on his back, but standing on his own two feet. Once, late in the match, Brennan is sure he has lost the fight on points, the boxer realizes that his task now is simply to endure the pain until the final round. “I think I can last” he tells his corner man. “I don’t want this bohunk to stop me (Hemingway 247). So, when he does get knocked down in the 11th round, he struggles back to his feet—taking a breather, on all fours, while the referee counts him down and shaking his head before rising up to face his adversary once again (Hemingway 247). It is at this point in the fight that a double-cross in the deal that has been made with Morgan and Steinfelt reveals itself, with all its brutality, to Jack in the ring. Hemingway, tells readers, Walcott….

backed Jack up against the ropes, measured him and then hooked the left very light to the side of Jack’s head and socked the right into the body as hard as he could sock, just as low as he could get it. He must have hit him five inches below the belt (Hemingway 247).

The pain of the blow is excruciating. Jerry notes that it looked as though “the eyes would come out of Jack’s head. They stuck way out. His mouth come open” (Hemingway 247). If Jack goes down or takes the foul, he wins the fight but loses the money he has bet on Walcott to win and, so, he must stay on his feet and continue to battle. This is endurance personified, yet, his ability to wield it is a manifestation of a stoic response that is rooted in the poise of the man himself. Thinking through the pain, and doing it quickly, Jack barks at the ref, “It wasn’t low…it was an accident…I’m alright” (Hemingway 247). Then taking a step forward, he tells Walcott, “Come on and fight” (Hemingway 248)). The younger fighter, now operating in a state of semi-confusion, hesitates, unable to believe that the man he has just hit in the testicles is still standing (Hemingway 247). But being waved forward by the referee, Walcott re-engages, hitting Jack twice, while the older man struggles to hold “his body in where it was busted” (Hemingway 248). And then, in one more great act of will, Jack begins to hit back. Jerry states…

His face looked awful all the time. He started to sock with his hands low down by his side, swinging at Walcott. Walcott covered up and Jack was swinging wild at Walcott’s head. Then he swung the left and it hit Walcott in the groin and the right hit Walcott right bang where he’d hit Jack. Way low below the belt (Hemingway 248).

Now, if he is going to achieve his own apparent goal of losing the fight, it is the younger man’s turn to endure the pain. Yet, unlike Jack, the more physically fit fighter grabs his swollen testicles and falls to the mat, rolling and twisting around in front of all who have come to watch the championship bout in the Garden that night.

Much like the way Shakespeare utilized a main plot with a sub plot in his dramas to highlight an important observation, Hemingway also supplies Fifty-Grand with a significant juxtaposition. Two men get hit in the testicles. One endures the pain, stays on his feet, and, by losing the fight on a foul, achieves his ultimate goal; in contrast, the other man grabs his balls, rolls around on the mat, and fails to achieve what he set out to do, crying and screaming like the proverbial little girl. Regardless of the difference in their age or physicality, the author’s message is clear: The biggest difference between the two fighters is their manhood; one is a man and the other clearly is not.

Fifty-Grand is a demonstration of how an individual achieves meaning in life through the dignity that self-control allows him to exert on a world he is cast into, one which operates at random and without purpose. Through the vital characteristics of a code that includes self-discipline, self-awareness, knowledge, skill, courage, endurance and poise, an animated organism becomes, what Binswanger argued was “a living being…. who dies its life and lives its death” (May 31). He is no longer a victim that the world acts upon, but an actor that asserts himself against forces that will eventually overwhelm, but never defeat him. This is the crux of the matter. It is not a quest for an unrealistic utopian vision of man, but rather a realistic assertion of an ideal that transcends the nightmare of chaos by applying form to it. That form, however, is made by man and in the making of it the individual becomes the man only he himself can create. To do less is to defraud him of both his manhood and his potential.

Glen Paul Hammond has a Master of Arts in English Literature from the University of Toronto. His publication credits include the educational book, The Literary Detective, and a forthcoming collection of short stories, entitled, Even the Moon is Frightened of Me, from Political Animal’s sister imprint, Crowsnest Books. Satirical cartoons and more of his writing can be found on his blog, SCRATCH.

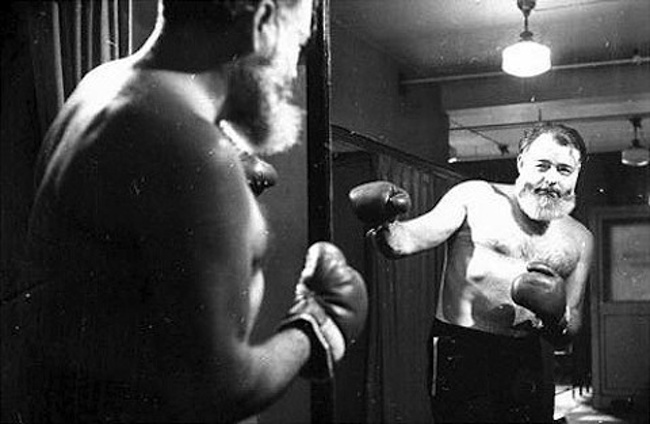

Image: Hemmingway boxing.

Works Cited

Hemingway, Ernest. “Fifty-Grand.” The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway, by Ernest

Hemingway. Simon & Schuster, 1998. pp. 231-249.

May, Rollo, et al. Existential Psychology. Random House, 1961.

Shakespeare, William. “Hamlet.” Four Great Tragedies. Penguin, 1963.

I have a different reading, part of it probably has something to do with an essay Robert Penn Warren wrote on the Hemingway protagonist. In short, it has to do with love; not romantic, but more encompassed by the notion of agape. If you can find the essay, it’s worth the read. I believe it was included in a collection of Warren’s essays. I lost the book years ago, but you may have access to greater resources than I. I don’t think, that Jack is driven by money, but the thought or knowledge that it is the only thing he can provide for his family.

It’s really a good story, one that I was unfamiliar with, but fortunately I have the Complete Short Stories – both the editor’s and Hemingway’s prefaces to the first forty-nine makes for a good read as well.

Hi Jake,

Thanks for reading the article and for your comment.

If I understand you correctly, I think we both agree—he is motivated by love for his family and it is this where he finds ultimate meaning and, yes, money is the means that he uses to be the provider for that family, and so expresses that love through this means. In this sense, the money has meaning because it is a necessary tool for the ultimate goal but not the goal in and of itself.

I will try to see if I can find the essay you mentioned, as it sounds interesting.

Thanks again,

G. Hammond

Actually, I think it’s more than that. you peaked interest in Hemingway again, an interesting comparison would be between his protagonist in Fifty Grand and Jay Gatsby with a view toward defining the American experience through both these authors – love goes beyond the familial. I won’t claim that the characters in The Battler are a better representation of the American ‘Hero”, if such a thing exists in post WWI American fiction, but there seems to be a clearer vision, or example of where Papa trends in his assessment of the role love plays in all of characters search for meaningful significance. Fifty Grand is a tremendous story, what I found incredible about the plot twist was the betrayal by the gamblers, I think you miss the lower blow as an attempt to throw the fight. Walcott is way ahead on points, the only way he can lose the fight is by fouling Jack. After Jack is fouled he has to brush off the low blow as nothing in order to keep Walcott in the contest. At this point, without another foul Walcott is assured of the win and Jack will collect his bet. Jack fouls Walcott, which is a pointless, but it disqualifies Jack from a bout that he has already lost – so in a sense, it’s a kind of poetic justice, it’s a meaningless gesture: one that could easily be viewed as petty or vanity. The story really is one of Hemingway’s better ones with respect to the complexity and fullness of his protagonist. Hemingway gives a lot in this story, and there are several themes that could be explored – of course, that’s what makes it a great story, and, again, thanks for resurrecting it. There is a great deal of beauty in it, lots of rules are broken, but Hemingway makes the story work, anyway. If you haven’t read The Battler, recently, you should give it another read. I think Paul Newman plays the beaten boxer in a film adaption of the Nick Adam stories – I can’t recall if the film was any good, but Newman’s play is so out of character that it’s worth a spin.

Hi Jake,

I haven’t read The Battler in years and can only say that the title sounds familiar; if it is the one I am thinking of, about the Bullfighter, than I remember being blown away by it when I first read it. Yes,again, I think we agree about the low blows and I hope I made that clear enough in the article. One of my fave stories from Hemingway is A Clean Well-Lighted Place. I am sure you have read it; it is a charming story with a lot of depth and all the usual philosophy.

Re: Gatsby: I teach Gatsby in my grade 12 class and we do compare Jack Brennan with him so it is interesting that you bring that up; we also add Willy Loman from Miller’s play into that mix. I think Hemingway can be distinguished somewhat from those two writers in a way that Miller himself articulated: Namely, that the American Dream is the centre point of all American writers writing in the United States. I think this is less true for the more internationally minded Hemingway but there is a lot of meat on the bones to compare with in those three main characters.

Best

Glen