By: Miroslav Tomoski from A Highway Journal

Losers is a continuing series of stories based on failed presidential campaigns, examining the ideas worth exploring from the candidates who almost made it to the White House and even those who never stood a chance.

NORTH CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA

857 MILES FROM HOME

The blond-headed MAGA-hat merchant in the parking lot looked familiar. He walked with a zig-zag sway in his shoulders. The same to-and-fro stride I had seen in a young man who sold Bernie Sanders masks a thousand miles away in Rochester, New Hampshire. His name was Tyler Tambasco, of Citrus County Florida, and he had just driven 36 hours from Nevada to South Carolina to sell red baseball caps to Trump supporters waiting in line for a rally at the North Charleston Coliseum.

Four years earlier, another rally was held at that same arena where presidential candidate Donald Trump, who was feuding with the Pope over Twitter, opened the event with a moment of prayer before promising to ramp up the torture at Guantanamo Bay.

“I think we should go much, much, much, further than waterboarding,” he said to a half-capacity crowd. The audience cheered. Trump was elected president. Four years gave way to another election cycle and I returned again to that arena where a much larger crowd of the president’s supporters were more fervent than ever and certain of victory.

“We’re going to have a landslide election,” Tyler said pointing to a line that weaved its way through the entire parking lot. Like many Trump supporters, Tyler felt there was no way the president could lose. Not with that kind of turnout. Not if all the arenas that Trump filled across America packed into the voting booths the same way they packed the surrounding bars after each event.

Months after election day, a majority of Trump’s supporters still believed he won. They believed it so fervently that the audience from a Washington DC rally on January 6th turned into a rabid mob that stormed Congress in an unsuccessful bid to overturn the election results by force. The true believers held out for divine intervention right down to Inauguration Day and many will continue to believe Trump won with the same sense of certainty with which they believe in God.

In the current era of American politics a simple idea loosed into the universe with a tweet form the right personality can quickly become an article of faith. A single half-truth dropped onto the internet can evolve into an entire way of life faster than any of us can control it. All of which makes the relentless meme machine a powerful force in politics today. It’s exposed several issues with both major American parties, but the challenges facing Democrats are not nearly the same as those facing Republicans.

Since the late eighties, the Republican party has slowly surrendered its leadership to professional opinion mongers who seized the wheel screaming decades before a President Trump was possible. Today, the most viral voices on the internet have inherited the legacy of cable news and talk radio personalities who’ve primed the party’s most fearful instincts for the past thirty years. It was these online and on air pundits who gave rise to and further fueled the rumors of a rigged election. Through their reporting on baseless rumors, they validated the ideas that fueled an angry mob.

As pundits have become the dominant thought leaders of the Republican party, they’ve opened the doors to a world of politics that’s entirely open to interpretation. They’ve given the party over to the Facebook comments section and the loudest tweets. To Qanon forums and YouTube channel researchers. In this new political environment, as long as an idea is viral enough to feel like the truth, it wields the influence to define what many Republicans choose to believe.

Despite the loudest opinions — or perhaps because of them — on November 3rd, 2020 Donald Trump lost. On Inauguration Day, he wished his followers “a good life” and said goodbye for now, but the ideas that drove millions of Americans to vote for him haven’t gone away. Donald Trump’s brand of politics hasn’t boarded a plane to Florida to live in exile on a golf course. That part of America was designed, by the pundits who built it, to outlast a president’s tenure and it will define the way Americans interact with one another for years to come.

Tyler Tambasco was working at a pizza parlor when he was offered the chance to travel across the country selling hats, scarves and even giant foam fingers to voters who have increasingly come to understand presidential politics as a team sport. He made his living off of the unwavering devotion of those who value their politics enough to display it on their backs. By the time we met in South Carolina, Tyler had crossed twenty-five states. He felt that the kindest people came from Arizona, he marveled at the natural majesty of the South West along the I-40 and he even spotted a castle somewhere along his travels through Kentucky.

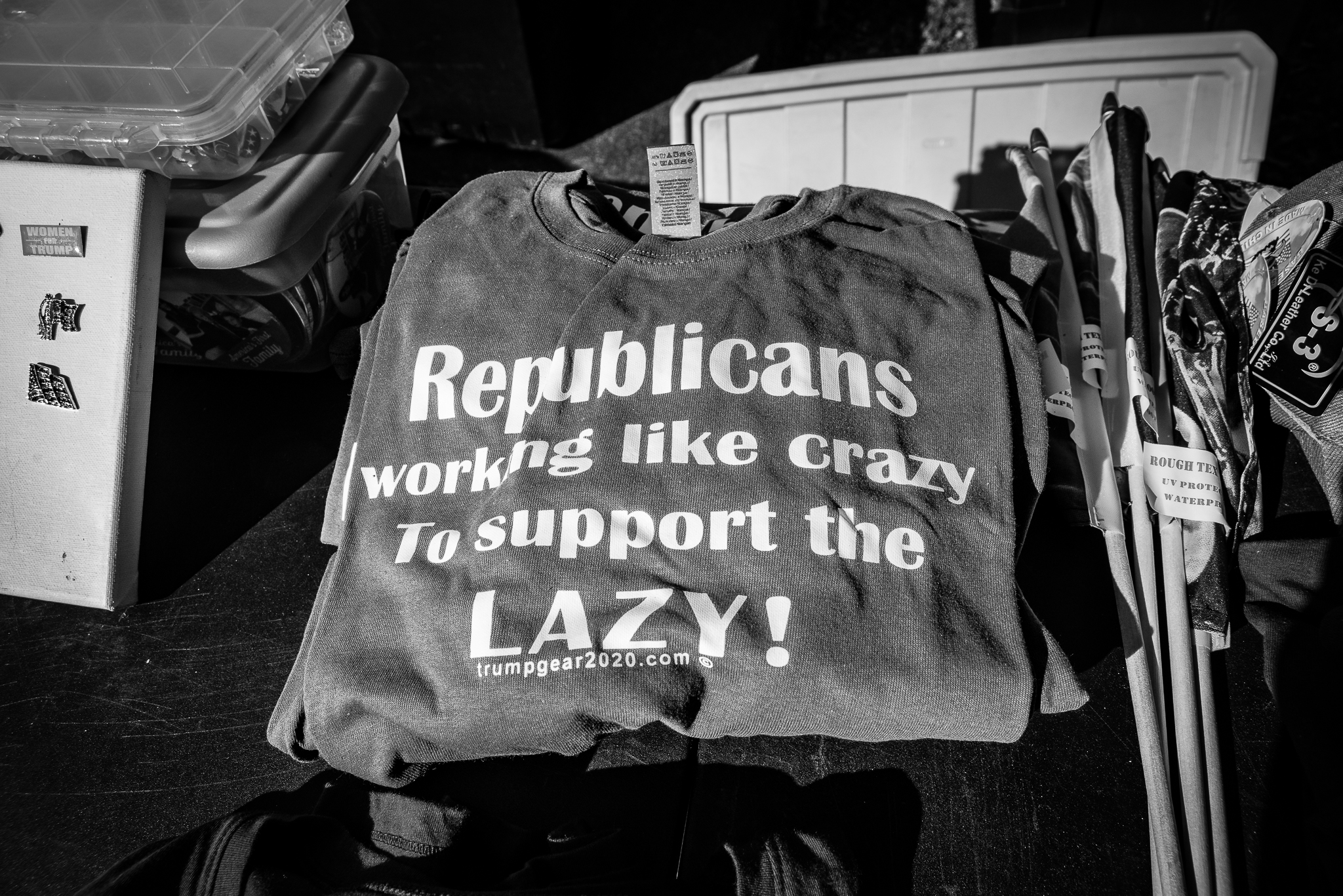

Political memorabilia merchants like Tyler were a common sight at rallies for presidential candidates, but nothing could compare to the open air bazaar of trinkets that followed Donald Trump from state to state. The roadside in front of the North Charleston Coliseum was sprawling with tabletop displays and concession trailers. Roadblocks had been set up by the local police for three blocks which gave the feeling of entering a maximum security theme park as barricades marked the temporary borders of Trumpland.

Some merchants followed the campaign like a wandering carnival, others spent the off season between elections at state fairs and still others — like Rob Cortis of Livonia, Michigan — had permanent shops in their home towns that sold presidential keepsakes year round.

“You look across at these people, how many red hats do you see? All you see are red tops,” Tyler told us, laughing at the strange turn of fate his life had taken; from pizza boy to traveling salesman. “I wouldn’t be out here if I wasn’t making good money. I could be in college playing baseball right now.”

As we surveyed the crowd, Tyler’s boss, Angel Shaske, approached him to suggest that they try a less competitive street corner. Within shouting distance, a couple of merchants were arguing about what the price of a MAGA hat ought to be. The going rate at most rallies was $20, but with at least fifteen vendors lining the same sidewalk someone had undercut the entire block at $5 a cap. A fight had broken out in plain sight of the customers before a gust of wind interrupted to blow their merchandise — fridge magnets, pins, stress balls, graphic tees and chew toys — clean off the tables and onto the street.

On an average day Tyler claimed he could sell around 200 hats and, at $20 a hat, an average day sounded good enough to give up on college baseball and get into politics. He hustled just as hard to sell Bernie masks, when we first saw him in New Hampshire, as he did selling MAGA hats to died-in-the wool, red-in-the-blood, southern conservatives. It didn’t matter much to Tyler which campaign slogan he sold. His main concern was to sell enough to make sense of a 36-hour drive across the country. What drove him and his fellow merchants from state to state were the rallying crowds on both sides of the political spectrum; eager to pay to display their team’s colors.

“I really wasn’t into politics before I got out here selling Trump hats,” he told us. “Politics is not my thing. I’m a big baseball guy, but I have people walking up to me expecting me to be an encyclopedia about Trump.”

Like the vast majority of Americans, the people Tyler interacted with most were his main source of news. Through his customers he could hear which memes were making their rounds on the internet, what the Clinton News Network — a common name for CNN among Trump supporters — was plotting and how real Americans felt about it. “I’m on the battlefield, so I speak to a lot of people,” he told us in a matter-of-fact way that asked ‘what better way to get your news than from the front lines of presidential politics?’

Though he sold hats and scarves to both Democrats and Republicans, Trump rallies were Tyler’s most profitable events, with the largest crowds who were most willing to buy. It meant that Tyler had become a Republican in a rather unusual way. Selling 200 MAGA hats at a time, he spent most of his working days speaking to Trump supporters. As he sold them slogans printed on hats, they sold him the ideas those hats represented and he too became a believer in the cause.

Angel Shaske didn’t need convincing. She believed that her president had gotten a bad rap. The media was relentless, she insisted, and they never reported honestly about the president’s real accomplishments. But above all, Angel believed that Republicans were just nicer people. “Look around you. Look at all the love,” she said, comparing the smiling faces beneath MAGA hats to the drive-by critics she encountered on the side of the road. “We get terrorized sometimes,” Shaske explained trying to convey the fear of working with the constant threat of marauding leftists. “They come over and try to stop our customers, they call the police on us for hate speech.”

“We’re screamed at,” Tyler added. “They’ll run you over, you know, people don’t even treat you like a human.”

For those who opposed Trump, a heightened state of tension was the absolute norm for four years as the red hat became as much a symbol of what President Trump stood for as it was meant to get a reaction. It’s not hard to imagine the sight of a MAGA hat setting off a few passers by and bringing their blood to a steady boil. The hat was a volatile piece of clothing and Tyler and Angel routinely carried stacks of them.

MAGA merchants will tell you that the hat wasn’t intended to be a symbol of division. They’ll explain that their enemies just have Trump Derangement Syndrome — a political strain of rabies brought on by the very sight of the former president. Their critics didn’t have legitimate grievances, they just had a politically charged mental illness, that’s all.

On the other hand, some of Trump’s supporters had grown into the idea that they could wear a red cap to get a rise. The reaction a hat got was reason enough to buy one. These were the supporters who waved flags that read “Make Liberals Cry Again” and happily solicited the roadside ‘fuck you’ from passers by that MAGA hat merchants have come to know as an occupational hazard.

For Angel Shaske and Tyler Tambasco, those reactions felt like personal attacks. They were inexplicable bouts of hostility that drove the two of them closer to President Trump. It was all the living proof they needed to believe that the left was out to get them, just as the left was out to get their president.

“I still have a right to my well-being and they want to stop us,” Shaske said. “I’m a 57 year-old woman raising an 11 year-old child, working on the side of the road. Don’t I have a right to make a living?”

The threat of the creeping left is a latent fear that’s been held by Republicans for decades. That fear reached a boiling point during the Trump era, but it’s fueled Republican ideology since at least the late 1980s. It’s the reason Roger Ailes created Fox News to give conservatives a voice they didn’t believe they had in the national press. The idea that liberals aimed to silence conservatives had been a common complaint among Republicans long before it became one of the wrongs that Donald Trump was meant to make right.

Even conservatives who hated Trump in 2016 felt threatened by the idea that their enemies were plotting to erase them from society without cause or warning. “I’m not a racist, I’m an artist,” A Los Angeles based street artist name Sabo told me in 2016 just before explaining why he felt Donald Trump was a conman. Sabo wasn’t into politics for the cult of personality. Instead, he felt he had lost something on a personal level. He was fighting for the Constitutional right to say whatever he wanted; a right he believed should come without consequence.

Unlike the roadside merchants who hustled through parking lots to sell mass produced Trump swag, Sabo sold custom made pieces like Barrack Obama toilet seats and rubber poo with Bernie Sanders name on it. He had gained a bit of fame in 2016 for artwork that featured his candidate of choice, Ted Cruz. Not long after that, the campaign abandoned him when Cruz realized that Sabo was fond of turning racial slurs into art.

For Sabo, being able to use racially charged words for their shock value was a hill to die on. It wasn’t because he was racist, he insisted, reminding me that he grew up in the south. He knew the weight of a certain word that carried a legacy in its wake. He would never really use that word, he insisted, but he just wanted to make a statement with his art.

“You need a sledgehammer to get people’s attention these days,” he explained. Modern media doesn’t take kindly to soft words. Not if the goal is to grab as much attention as possible. Not if you intend to compete with the relentless stream of information that flashes across millions of faces as they scroll though the day-to-day news feed.

For a brief trending moment of infamy, Sabo found a way to get the internet to stop scrolling. That’s what it was all about. Success in the modern world of political commentary required controversy. Sabo wasn’t trying to be a racist, he explained, he was just trying to be offensive.

“I like it when I walk into a room and I’m wearing a shirt that says ‘Mohammed Is A Homo’ and punk rockers come up to me and says dude, I wanna take a picture with you,” he said.

Countless other commentators, writers, artists and opinionators are competing for that same level of notoriety. They want something as abrasive as a MAGA hat to catch the eyes and ears of viewers, readers, users and followers. A sledgehammer, as Sabo called it, because shock value works best when you’re trying to get the attention of a crowded space. It’s extremely effective, but it’s also just extremely frightening when shock value becomes a guiding force in politics.

The best of that content today looks like Fox’s Tucker Carlson, who’s prime-time show did so well in the wake of George Floyd’s death that some Republicans suggested, in earnest, that he should run for president. Focusing almost exclusively on the riots that resulted from one police shooting after another, that summer Tucker climbed the viral ladder to host the most watched cable news program in history.

“A small group of highly aggressive emotionally charged activists took over our culture. They forced the entire country to obey their will,” Carlson said of the Black Lives Matter movement, claiming — for maximum effect — that they had formed the most powerful political party in the country.

In an aggressively punctuated tone, Carlson’s huff-and-puff monologues channel the half-truth style of the original right-wing radio personality, Rush Limbaugh. With millions of Americans tuning in to hear what he would say next, Carlson and his Fox collages were reaching out to a faithful audience that Limbaugh had cultivated and primed long before the first Fox program aired.

“[He] paved the way for people like me…and so many others,” Fox’s Sean Hannity said in 2018, celebrating 30 years of The Rush Limbaugh Show.

A one-time amateur stand-up comedian, who took over the ideology of an entire political party, Rush set the model for conservative opinion content when his radio program first aired in 1988. Railing against feminists, the LGBT community and even the endangered spotted owl, Limbaugh rose to stardom by convincing his listeners that the creeping left was out to destroy their way of life. To change the culture. To force the country to obey their will.

Limbaugh’s heated opinions caught on so quick that in 1992 former President Ronald Reagan honored the radio host by calling him, “the number one voice for conservatism in our country.”

Today, conservative media is packed with professional mimics of Rush Limbaugh. Experts of their own opinion like Carlson and his Fox colleagues, Laura Ingram, Sean Hannity and newer voices like Ben Shapiro and Tomi Lahren. Pundits like Mark Levin, who starts his Sirius XM radio show every day by reminding listeners that he’s broadcasting from the bowels of an undisclosed building. Dinesh Desuza, who in his latest film, Trump Card, claims that Democrats are working with radical Islamists to hang a Soviet flag above the New York Stock Exchange.

These aren’t wackjobs on the fringes of the internet, they are regular floating heads on Fox, they are best-selling authors, they run the most popular conservative media outlets in the world. As Ben Shapiro once told the BBC’s Andrew Neil, “I’m popular and no one’s ever heard of you.”

These voices swing sledgehammers daily for an audience that believes they are watching the news with minimal bias. According to the 2020 American Views survey conducted by Gallup and the Knight Foundation, only 34 percent of Americans are concerned that the news source they rely on could be biased. That’s a frightening level of trust placed in a handful of celebrity political commentators whose business model falls just short of delivering the news.

Behind-the-scenes, producers and managers like Jeremy Boreing, who crafted Ben Shapiro’s wardrobe to appeal to young conservatives, openly admit that the primary concern of these political personalities is not accuracy in reporting.

“The business model is not activism, or even news,” Boreing claims to have told Shapiro before launching him to conservative talk stardom “The business model is personality.”

For the past thirty years the Republican party has slowly surrendered itself to a seething mob of personalities who’ve built their careers competing to produce the most outrageous opinions. To inherit Limbaugh’s influence over the party. In essence, Donald Trump was not responsible for creating the party of alternative facts. The current ideology of the Republican party was crafted over the airwaves, loudly and relentlessly, evolving alongside new media and raising two generations of conservatives who came to elect a celebrity like Donald Trump whose voice perfectly matched the tone of the voices they had come to trust.

Brian Rosenwald, an historical journalist, lays it out in his book Talk Radio’s America: How An Industry Took Over A Political Party That Took Over The United States. With massive audiences listening to their programs each day, conservative pundits came to define the way voters saw the world and, as a result, could sway their votes. What began as a way for politicians to get some friendly PR, quickly turned into a hostage situation that the party could no longer control.

“In the Clinton days, hosts primarily used their influence to advance the party’s goals. Under Bush, hosts clashed with the leadership more frequently and used that influence to hold members accountable…by the time Obama was in office hosts could wield their influence to evict from the party the ideologically indefensible…By the end of 2012, Republicans [in office] feared what they had created and could only hope to govern by spinning their votes [in Congress] to avoid backlash.”

In the era of Trump, these media personalities became the party’s leadership. They were the voices even the president watched and listened to and tweeted about as often as real Americans.

These personalities created the slogans that were printed on shirts and hats to keep people like Tyler Tambasco and Angel Shaske in business. They were the voices that echoed back through their customers and made them eager to buy the scarves and buttons and foam fingers. The voices that motivated the fearful disposition of American conservatives.

To Republicans who listened closely to these personalities, the issues attached to the Democratic party were something to be feared. It must be fearful, after all, to believe that your enemies are in favor of murdering babies, stealing your guns, promoting death panels as part of healthcare, dissolving the concept of family, condoning riots, disrespecting the flag and destroying the culture of America.

One issue in particular that illustrates the fearful spin of conservative punditry and it’s influence on Republican party policy is climate change. It’s an issue that’s been closely associated with leftist plots to destroy the economy and take over America since the early days of Limbaugh’s show. So much so, that it’s led Republican voters and lawmakers to completely deny the issue exists rather than offer practical policy alternatives.

“I happen to believe in God. I believe in a loving, brilliant.” Rush said on his program in February of 2011. “I know this – there is no way, I don’t want to sound like a simpleton here, but there is not – it is not possible that we would be created by a creator in such a way that we would destroy by virtue of our created existence our own planet and environment. It just doesn’t compute and yet that’s what these people are trying to tell us.”

Confident in the belief that human beings couldn’t possibly have an effect on their surroundings, Rush painted environmentalism as a liberal plot to take over the country. A few months later, in May of 2011, he laid it all out saying, “the left marches on, not educating but indoctrinating. And so now schools will be indoctrinating children to be good environmental citizens, which means wards of the state.”

All of which uncharacteristically breaks from a long standing Republican tradition of conserving the environment. From Teddy Roosevelt who founded the National Parks Service, to Richard Nixon who created the Environmental Protection Agency, conservatives aimed to conserve the country’s natural beauty. Less than a year after Limbaugh first shouted into a microphone, Republican presidential candidate George H.W. Bush ran a winning camping saying, “Those who think we’re powerless to do anything about the greenhouse effect are forgetting about the White House effect. As President, I intend to do something about it.”

Having risen to fame just as the Cold War was ending, Rush and the voices that followed his model were now painting the Joseph McCarthy-esque picture of the enemy from within. The leftists at home wanted to control America, to destroy the pillars of capitalism and democracy through a climate change hoax. It was such an effective message, backed by big donors like the Kochs, that it forced Republicans to abandon something they championed just a couple’s years earlier.

As recently as the 2008 election, Republican candidate John McCain was boasting that his cap and trade plan for climate change was better than what Barrack Obama was offering.

Today, the Republican interpretation of the Green New Deal is a strange dystopian mixed-bag of rumors. It’s a policy that conservative voters have chosen to oppose with the false-belief that they’ve been properly informed.

When Yale University conducted a year-long study on American’s opinions of the Green New Deal, 64 percent of Republicans supported the plan after seeing it for the first time in December of 2018. By April of 2019, Republican support for the Green New Deal fell to 32 percent. The study found that Republicans had heard much more about the policy than Democrats because conservative outlets covered it far more than their counterparts. That coverage, however, was questionable at best.

For more than a year since the 2018 midterm election, Fox ran with the idea that Democrats want to slaughter every cow on earth to save the planet from farts. It was their choice approach to explaining the Green New Deal and it came from a literal reading of a joke made in a leaked rough draft of the policy.

“The Green New Deal is a religious document,” Tucker Carlson told his audience with a straight face. “It punishes America for the sins of its prosperity. The only atonement it offers is turning over control of the entire US economy to the Democratic party. That’s the indulgence they require. They’re using moral blackmail to get it. Theocrats always do.”

Others at the network had a little more fun with their interpretations of the policy calling it a secret socialist plot from Canada, put together by Elliot Page and Naomi Klein to destroy capitalism in America.

“This is a real proposal,” Sean Hannity said, scaring millions of people in a single night into thinking their lives were threatened by “real ideas from real lawmakers in the new radical extreme democratic socialist party of America, beyond dangerous, beyond scary.”

Except it wasn’t. In the real world, the Green New Deal that pundits were hyping as a Stalinist wet dream did nothing at all of substance. It was a work very much in progress. A vague non-binding promise made by Congress to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030. It was an ambitious pledge made by Democrat leaders in order to get a group of young protesters out of Nancy Pelosi’s office. The pledge for a Green New Deal was a promise to make drastic changes without specifying how.

That was perhaps the most legitimate criticism Republicans could have made. That their rivals pledged to combat climate change in a big way without specifying how. If it were a simple debate about policy Republicans might find a way to compromise or provide a better alternative. But when the claim is that climate change is a hoax perpetuated by an enemy that is trying to make hamburgers illegal, the parties are no longer having the same conversation. It’s not a disagreement on how best to address an issue, but a debate that questions the current state of reality.

Climate change is one issue in which you can see a clear shift of Republican policy matching perfectly with the influence of conservative pundits. Many have characterized it as shift to the hard right, but in truth there is very little in the way of real ideas guiding these outrageous statements. It’s not inherently conservative or right wing to routinely say incredibly asinine things. Instead, it’s an ideology that is solely guided by opposition. A mentality that says ‘if my enemy believes it, it must be a lie.’

“I don’t need scientific proof because to me the people who are promoting manmade global warming are a bunch of frauds,” Rush told his audience in March of 2011. “They are liberals, they lie. It’s not a generalization. It is an undeniable truth of life.”

In spite of reality, conservative media’s opinions have a very real effect on their audience. They create a divide where one might not exist, making it impossible to know who to trust.

“I don’t believe in the Green New Deal,” Angel Shaske told us. “I want clean water and clean food too, but I don’t want the government to control it. I don’t want them to control it.”

When the most influential voices within a party are allowed to frame the world based on their opinions it gives license to their audience to fill in the details with their own version of the story. People like Hannity, Carlson and Limbaugh are trusted with the truth, but if the truth is up for grabs to the very people who are supposed to tell it, then it doesn’t matter where the lie comes from. A loosely interpreted version of real events is no more useful if it comes from a prime time cable host, a conspiracy theory forum or a MAGA hat merchant in a parking lot. But if the information that passes as news is just as reliable as what you hear in the parking lot, trust in authority of any kind is completely dissolved and the party that embraces a cavalier approach to facts becomes leaderless. It allows Qanon forums to question the results of an election and incite a mob to rebel.

Like the worlds most terrifying game of telephone, the real world influence of political personalities is felt in the opinions passed down from pundits to internet forums to rally goers to people like Angel Shaske who traveled the country spreading the gospel of Rush.

“I think [Democrats] are liars, they will take anything — the sky is blue, they will say it really is purple…” Shaske said, explaining the treachery of her fellow Americans. “I’ve got real science, not something that was paid for and they only study what they ask you to study.”

Republicans today have a uniquely fearful view of their political opponents. It’s not a standard rivalry of reconcilable differences that can be hammered out through civil debate. It’s a genuine fear that the other party is out to destroy their way of life. It can be seen in those who attended rallies believing they are fighting the enemy among them. Like Chris Sawyer of Barrington, New Hampshire who told us that, “Democrats have weaponized the the federal government, they’re trying to make it a one-party system and turn our country, a great nation, into a socialistic communist type of society where, we don’t have any freedoms.”

It’s a hopeless pessimism that can run away with itself in the comments section of an article or places like 8chan where Qanon theories are born. In the post-Trump era, the people who subscribe to those theories still occupy the halls of power. From Ted Cruz’s impassioned speech about election rigging being the reality for half the country to newly elected Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s past support for claims that Jewish space lasers are responsible for forest fires, the champions of an alternate reality are here to stay. For promoting absurd theories, Taylor Greene was removed from committee positions by the House, but only 11 of her Republican colleagues voted to do so, while an Axios poll showed that more Republican voters approve of Taylor Greene than her moderate counterparts.

“Every time you turn on the radio or the TV that’s all you’re hearing is how bad the other side is,” a friend of Sawyer’s named Darren Ramsden, told us. “People are left in the middle either trying to make a decision based on just what they’ve heard or go and figure out if there’s some other story, some other angle, that they haven’t been told and so they start reading shit on the internet.”

It gives rise to a paranoid sense of terror that comes across in places where conservatives feel most comfortable sharing their thoughts. It comes across in the parking lot at Trump rallies and social media platforms like Parler where users named BasedRedPillZeus post comments like:

“I’m going to be straight up with you – there needs to be a great cleansing. I’m talking massive bloodshed. I’m not using hyperbole. The deep state is so massive, the corruption is so deep – the only thing that can root out this great evil is killing. I wish it wasn’t the case. What the fuck is there to live for? Masked up, chipped, forcefully inoculated, put on UBI, it will NEVER END.”

The true damage that is done by allowing the opinions of media personalities to play such a primary role in a political party’s rhetoric is that those theories taint the partial truths on which they are sometimes based. Media personalities sometimes highlight real and serious problems that a society ought to address, but can no longer approach from a realistic perspective because their point of view is designed to stoke anger not to solve problems.

If there’s a lesson Rush Limbaugh has taught Americans it’s that a lie told once can be harmless. A lie told often can make a successful career. And a lie told for three hours a day, five days a week, for thirty years can rot the collective mind of a nation.

The point of stories told by media personalities is that they have no end game. There is no resolution to the problem of the creeping left or Washington elites or culture warring liberals. Roaming the parking lot that afternoon with a stack of MAGA hats in hand, Tyler Tambasco and Angel Shaske were counting on a win for Donald Trump. A win meant more rallies, more road trips, more hats and more customers, but a loss may be better for them in the end. After all, MAGA merchants and pundits alike aren’t selling solutions, they’re offering something to root for. Their customers are perpetual outsiders, fighting an enemy that was never designed to be defeated because the day that America is made great again and there are no liberals left to trigger is the day that the hat loses its meaning and the pundits have noting to say.

This article was updated to include current events involving Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene that occurred after its initial publication.

Losers is a continuing series of stories based on failed presidential campaigns, examining the ideas worth exploring from the candidates who almost made it to the White House and even those who never stood a chance.

Image: Photo by Lance Monotone.

POLITICAL ANIMAL IS AN OPEN FORUM FOR SMART AND ACCESSIBLE DISCUSSIONS OF ALL THINGS POLITICAL. WHEREVER YOUR BELIEFS LIE ON THE POLITICAL SPECTRUM, THERE IS A PLACE FOR YOU HERE. OUR COMMITMENT IS TO QUALITY, NOT PARTY, AND WE INVITE ALL POLITICAL ANIMALS TO SEIZE THEIR VOICE WITH US.

Leave A Comment