By: Claudia Hauer

The themes of homecoming and the father-son relationship have received a lot of literary attention recently. Marilynne Robinson just published Jack, the fourth novel in her Gilead series, about the Ames and Boughton families’ complicated stories of homecoming, fatherhood, and sonhood in an American small town beset by racial and religious tension. The tensions between fathers and sons, and the son’s struggle with finding his way back home are timeless and cross-cultural, and trigger some of the deepest issues we have with identity and belonging. Look to any cultural literary tradition, whether of the West, the East, or the Middle East, and you will find tales of fathers, and those sons who attempt to find their way back into their recognition.

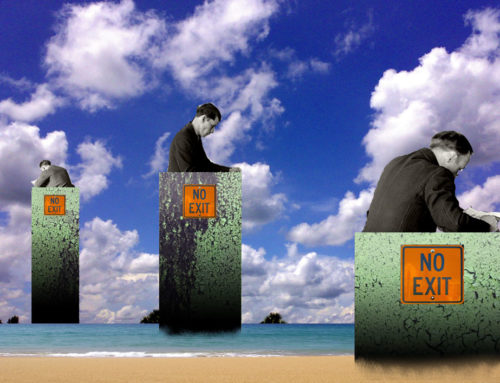

Songs by the Canadian musician Leonard Cohen, who died four years ago at the age of 82, suggest that he grappled with the father-son relationship, and with the emotional desire for home and homecoming. Cohen might not at first seem to have much in common with an ancient Greek figure, but a comparison yields rich and provocative similarities between Cohen and Odysseus, the hero of Homer’s poem of homecoming, the Odyssey. Odysseus, a fictional warrior with talents, like Cohen, as a language-artist, is better-known for his homecoming as a husband, but he ultimately returns to his broken father as the honored and beloved son. Homer’s and Cohen’s poetry have some surprising parallels on this theme. The fictional character of Homer’s ancient epic and the real-life contemporary poet and musician speak to each other across time and space. The following comparison illustrates the many surprising ways that the ancient Greek classics still speak to our contemporary struggle to find expression for the complex relationships that come with being human.

For the author and her family, Leonard Cohen’s death was one of those “who does not remember where they were when they heard this news?” moments. Cohen’s husky tones and memorable poetic phrasings had been a soundtrack to our lives. His death, coming as it did only days after the results of the 2016 U.S. presidential election were announced, filled us with nostalgia and despair. Who would sing for us now? It was the day the music died. Cohen’s death touched our homes and our hearts.

Cohen is known for his artistic struggle with questions of faith, redemption, doubt, and loss. At times in his work, as well, Cohen’s deep engagement with the father/son relationship emerges. Cohen lost his own father at the age of nine. 61 years later, at the time of the Dear Heather release, we can still see Cohen grappling with his quest as a son. At the end of the song “To a Teacher,” Leonard Cohen sings:

I have entered under this dark roof

As fearlessly as an honoured son

Enters his father’s house.[1]

Cohen’s song is a love song and a lament for the plight of Abraham Moses Klein, whom Cohen admired, and who served as teacher and mentor for Cohen’s great friend, Irving Layton.[2] The song is nominally about Klein’s dementia, but it is also a poet’s reflection on how the artist will always struggle against the darkness of silence and creative paralysis. The artist recognizes the inner abyss that always lurks as the flip side of creativity. Cohen seems to be claiming that he can feel at home with this darkness. He enters into Klein’s madness as fearlessly as the honored son enters his father’s house.

The image of an honored son entering his father’s house, sure of his reception, is evocative of many iconic symbols. Theologically, it evokes the parable of the Prodigal Son. In the arts and in literature, it is a metaphor for coming home.

Coming home is itself a rich philosophical problem. While it is a logistical matter to travel and arrive at one’s childhood home, it is an altogether different matter as to whether in your homecoming, you can be at home in a meaningful way. The ancient bard Homer takes up this problem in the epic poem The Odyssey. Emily Wilson’s remarkable new translation of this venerable Homeric epic has called new attention to the delicacy and fragility of the problem of homecoming.[3] Wilson’s language tenderly calls attention to the details of recognition and belonging that define the homecoming process, particularly as it pertains to Odysseus, the tale-spinning warrior attempting to get home. Odysseus’ warrior comrades at Troy have all been unable to make coming home into something meaningful. Ajax committed suicide, Agamemnon was murdered by his wife and her lover, Menelaus has fits of wild anger and has to be medicated by his reclaimed Helen. Nestor lives for the glory days, and also has an anger problem. Only Odysseus, of that group of commanders, is able to turn coming home from war into something profound.

Odysseus has been gone for twenty years – ten at Troy and ten getting home. This time span turns the problem of recognition into something urgent and tenuous. Penelope’s process through the stages of recognizing her husband is a study of how the emotions, the intellect, the memory, and ultimately, the spoken word all must find harmony in order for recognition to be complete.

There is another passage in the Odyssey, though – less studied – but no less interesting as a recognition scene. It occurs near the end of the poem, when Odysseus walks out to find his father on his family’s remote orchard in order to tell his father that he is home. Odysseus pretends to be a stranger, to learn whether his father still grieves his son’s absence. The father falls to the ground in grief. Odysseus pulls him to his feet and identifies himself as the beloved son. He conveys the truth of this to his father by naming the fruit trees that have grown up in the orchard, trees that his father planted for his son when Odysseus was just a baby. Wilson translates:

When I was little, I would follow you around the garden, asking all their names.

We walked beneath these trees, you named them all, and promised them to me.

Odysseus still remembers the numbers of the seedlings. “ten apple trees, thirteen pear trees, forty figs, and fifty grape vines,” he recounts. His father is overcome. Through Odysseus’ recollection of the numbers of young trees, his father recognizes him, and Laertes rejoices in the return of his beloved and honored son.

As an act of recognition, this scene is evocative of a metaphysical aspect of the human condition. Humans are able to recognize a tree that we last saw as a seedling twenty years ago. How is the human mind capable of this? Philosophers have debated this capacity for thousands of years. For the metaphysician, it is a problem to be solved. For the artist, it is a matter for wonder and awe. For the returning warrior son, it is the basis for restored identity. Recognition has the power to pull us away from the brink of madness. We can find these motifs both in Homer’s story of Odysseus and in Leonard Cohen’s self-conscious stanzas, despite these poems being separated by thousands of years. The timelessness of the theme of recognition focuses our human story.Odysseus, like Leonard Cohen, was no stranger to the abyss. Odysseus’ journey home from war included a lonely seven-year stay on Calypso’s island, a visit to the land of the dead, and encounters with monsters and the darkest demons of his proud nature. His homecoming was fraught with danger and violence. Perhaps the moment with his father under the fruit trees was Odysseus’ first glimpse that the possibility of coming home to a world of peace and plenty could be realized. He recalls his toddler days, and following his father around with innocence and curiosity, just as Cohen recalls the teacher-figure Klein in his prime.

Cohen’s poetry and music convey a keen sensitivity to feelings of longing and the frustration of unanswered questions. Cohen never had the chance to return as the honored son to his blood father’s house. His ode to Klein acknowledges that this now-broken father-figure once meant a great deal to him, and that Cohen’s own ability to engage in the act of recognition allows him to see in Klein’s madness his earlier creativity, and the inspiration he generated.

Odysseus does make it home, but it’s intensely hard. Homer’s poem celebrates his ability to be at home despite his memory of previous madness, and all that has befallen him. Even in the midst of this touching scene among the fruit trees, Odysseus, his father, and his son are still in grave danger of violence from the fathers of the slain suitors. The friction, the effort, the striving never cease throughout this epic poem, as they never ceased for Leonard Cohen.

Despite being separated by thousands of years, Cohen’s story and Odysseus’ hold many parallels. Homecoming for the artist and the warrior takes courage. Perseverance. Love. Perhaps most importantly, the ability to hold one’s sanity in the face of the one question that can never be answered: Do we sing a holy or a broken hallelujah? Cohen’s ability to invoke our relationship with the characters of our past resonates poetically, and four years after his death, also socially. The ability to accept that we are bound to the voices of our collective and individual pasts is perhaps one key to salvation in this political age of static, prosaic competition to have the loudest and bluntest voice.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BTviN-lpGYg

[2] https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/leonard-cohens-montreal; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._M._Klein

[3] Homer. 2018. The Odyssey. Transl. Emily Wilson. W. W. Nortion & Company, Inc.

Claudia Hauer is an expert on liberal education, military education, and the relationship between the two. She teaches humanities, science, and languages at St. John’s College, and taught moral philosophy at the United States Air Force Academy, where she held the Lyon Chair in Professional Ethics. She has a BA in Classical Studies from the University of Chicago, and an MA and PhD in Classics from the University of Minnesota. She is the author of Strategic Humanism: Lessons on Leadership from the Ancient Greeks (Political Animal Press, 2020).

Image: The Reunion of Odysseus and Telemachus (1880) by Henri Lucien Doucet.

POLITICAL ANIMAL IS AN OPEN FORUM FOR SMART AND ACCESSIBLE DISCUSSIONS OF ALL THINGS POLITICAL. WHEREVER YOUR BELIEFS LIE ON THE POLITICAL SPECTRUM, THERE IS A PLACE FOR YOU HERE. OUR COMMITMENT IS TO QUALITY, NOT PARTY, AND WE INVITE ALL POLITICAL ANIMALS TO SEIZE THEIR VOICE WITH US.

Leave A Comment