By: Anthony Sean Neal An essay from 1000-Word Philosophy

Race today is often presented as a social construct. But social constructions, as Black people know all too well, can create real existential crises.

Philosophers of the Black Experience[1] writing during the Modern Era of the African American Freedom Struggle (1896-1975)[2] engaged questions of freedom, existence, and the struggles associated with the experiences of being Black in America.

During this period, Black socially-minded thinkers focused their energy on the meaning of being human and how the social construction of race, for them Blackness, created very real obstacles for a flourishing life. This essay reviews four thinkers from this era to demonstrate their attention to the existential crisis of Blackness, understood as the oppressive experience of Black people living in America: W.E.B. DuBois, Alain Locke, Howard Thurman, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

1. W.E.B. DuBois

Plessy vs. Ferguson[3] was the 1896 Supreme Court decision that legalized the “separate but equal” educational policy in the United States. It was a pivotal case for cementing into law, at least for the moment, the legal conditions for the social construction of Blackness.

W.E.B. DuBois’s 1896 The Suppression of the African Slave Trade was published in the same year. DuBois’s work set forth a prototypically new direction and era in the struggle for survival and freedom among Black people in America.

Before 1865, within the institution of slavery, escape was the primary focus of the Freedom Struggle. After the end of slavery, the experience of continual discrimination and racial violence made it clear that the fragility of black existence extended beyond the plantation into all areas Black people occupied. This forced the need to rethink the requirements for Black survival in an oppressive society.

Education became thought of as a possible weapon for the struggle against Jim Crow, the set of policies and conditions enforced to maintain the separate status and class distinction of Black people, also called Black Codes. DuBois’s advocacy for education as a means of struggle shaped the scholar/activist model among Blacks. The framework used to encourage this effort among others can be found in Du Bois’s essay on “The Talented Tenth.” In this model, highly educated blacks aimed to use their acquired knowledge for the struggle for freedom and exposing the crisis of anti-Black racism.

2. Alain Locke

Alain Locke[4] also sought and used education to work towards the goal of freedom. His focus was chronicling the artistic productions of contemporary artists, although he also chronicled the artistic achievements of Africans throughout history. He considered this his effort towards freedom and the African American struggle.

Locke sought to initiate a discussion about the value of Black folk culture, while simultaneously connecting this culture to its predecessor in Africa. Towards the end of his life, he lamented over what he saw as disappearing Black folk culture. He wrote, “the high cost of prejudice, to which we had all but become accommodated, is now being compounded by the high price of integration. Together they add up to a capital levy [a drain on resources], and strain to the utmost on our artistic resources and our intellectual morale.”[5] For Locke, this loss of Black folk culture was equivalent to the loss of Black communal strivings for freedom.

3. Howard Thurman

Howard Thurman,[6] was struck by how the experience of segregation instigated a feeling of self-rejection. He asked, “What does it mean to have a cheap self-estimate?”[7] He argued the experience of being Black in America created a type of fragmented self-consciousness or alienation from the true or human self.

His early philosophical activity focused on thinking through whether or not Christianity had anything to say to oppressed people in their oppressed condition. Thurman argued that Christianity, as practiced in America, was fundamentally racist. He argued that the solution for those facing deeply entrenched racism was for Black people, as well as white people, to embrace love as a core value and religious aspiration: anything less might lead to destruction.

4. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was also concerned that misery constantly haunted Black people.[8] He wrote Why We Can’t Wait to depict the effects that the experience of blackness was having on even Black children. King’s observation was that the existential crisis of oppression in America was so pervasive that even the imaginations of Black children were being deprived of hope for a good and flourishing life.

King’s 1963 “I have a dream” speech and the vigorous repetition of its title phrase imposed an idealist response to the existential concern of the fragility of life. The intent of this response was to establish that the activity of reconceptualizing society was not necessarily a top-down or white-only activity. His goal was to elicit an active response to the conception of reality he put forward. This active response required that community activists began to mobilize grass root activities such as demonstrations, boycotts, and sit-ins to force the new reality into being.

The Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964 is an example of this active response. In defiance of the present reality, white students from the North and Westcoast assisted Black citizens in a grassroots struggle, using education, so that they could gain the right to vote.

5. Conclusion

This brief overview demonstrates some of the most important efforts of Black thinkers to wrestle with the notion of Blackness and the struggle for survival in America during the Modern Era.[9] This struggle is captured in their examination of Black existence and their constant fight for the ability of Black people to live a life of their choosing.

Their concerns can be applied to anyone living in an oppressive environment, especially in light of present-day concerns. These concerns include questions about the relationship between education and a flourishing life, the value of immigrant cultures, racism within evangelical Christianity, and the proper methods of struggle. In many ways, the existential concerns of the Modern Era of the African American Freedom Struggle remain part of our current struggle.

Notes

[1] Philosophers of the Black experience include writers and thinkers who engaged in philosophically-reflective analyses of the Black lived experience.

[2] The Modern Era of the African American Freedom Struggle is defined by the events of the Plessy v. Ferguson decision (1896) to the end of the Vietnam War (1975).

[3] See Anthony Neal, Common Ground: A Comparison of the Ideas of Consciousness in the Writings of Howard Thurman and Huey Newton (Trenton: Africa World Press, 2015), x. The Modern Era is explained here further.

[4] Locke was the first Black Rhodes Scholar and the first Black Harvard Ph.D. in Philosophy, and former chair of philosophy at Howard University.

[5] Alain Locke, 1952. “The High Price of Integration: A Review of the Literature of the Negro for 1951,” The Phylon, 7.

[6] Thurman was a mentor to MLK, Jr. and the first Black Dean of Marsh Chapel at Boston University.

[7] Howard Thurman, The Luminous Darkness: A Personal Interpretation of the Anatomy of Segregation and the Ground of Hope (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 24.

[8] Martin Luther King, Ph.D., Why We Can’t Wait, (Boston, MA: Beacon, 2011),

[9] Howard Thurman, The Luminous Darkness: A Personal Interpretation of the Anatomy of Segregation and the Ground of Hope (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), x.

References

DuBois, William Edward Burghardt. The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America 1638-1870. 1896. Longmans, Green, and Co.

DuBois, William Edward Burghardt. The Souls of Black Folk. 1903. McClurg.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. Why We Can’t Wait. 1963. Signet Classics.

Locke, Alain. “The High Price of Integration: A Review of the Literature of the Negro for 1951.” 1952. The Phylon.

Thurman, Howard. Jesus and the Disinherited. 1949. Beacon Press.

For Further Reading

Moses, Greg. Revolution of Conscience. 2018. Brookline.

Harris, Leonard. The Philosophy of Alain Locke. 1991. Temple.

Chandler, Nahum Dimitri. The Problem of the Negro as a Problem for Thought. 2013. Fordham.

Neal, Anthony. Howard Thurman’s Philosophical Mysticism: Love Against Fragmentation. 2019. Lexington.

Related Essays

Existentialism by Addison Ellis

Camus on the Absurd: The Myth of Sisyphus by Erik Van Aken

Marx’s Conception of Alienation by Dan Lowe

Reparations for Historic Injustice by Joseph Frigault

The Ontology of Race by Abiral Chitrakar Phnuyal

Anthony Sean Neal is an Associate Professor of Philosophy and a Faculty Fellow in Shackouls Honors College at Mississippi State University. He was inducted into the Morehouse Collegium of Scholars in 2019. He is also the author of Common Ground: A Comparison of the Ideas of Consciousness in the Writings of Howard W. Thurman and Huey P. Newton (Africa World Press, 2015) and Howard Thurman’s Mystical Philosophy: Love Against Fragmentation (Lexington, 2019). His current book project is entitled, “The Modern Era.” https://msstate.academia.edu/AnthonyNeal

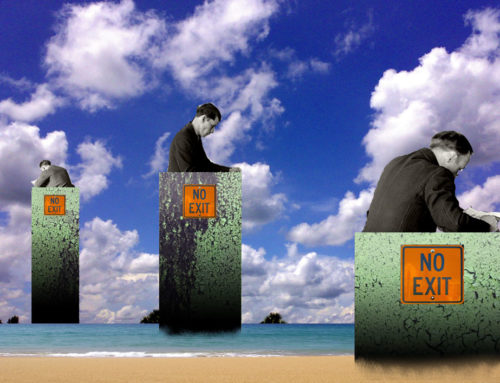

Image: PAM illustration based on image of W.E.B. DuBois, Alain Locke, Howard Thurman, and Martin Luther King, Jr. via 1000 Word Philosophy.

Leave A Comment