Art of Politics, Politics of Art, A Series By: Jeanette Joy Harris

In this series, Jeanette Joy Harris looks at how artists around the world are using public and participatory art forms to describe, analyze, and influence contemporary politics.

In a rare case of agreement, politicians and artists alike are casting doubts on the viability of the International Criminal Court (I.C.C.). In a statement last week, U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton announced that the U.S. might sanction the I.C.C. because it is considering prosecuting Americans for war crimes in Afghanistan. This stance is also one of the major concerns that underlines Milo Rau’s performance and film work “Congo Tribunal,” and Chris Weitz’s recent film “Operation Finale,” both of which question the potency of the I.C.C.

In September, it celebrated the 20th anniversary of the Rome Statute, the treaty that established a standing court to address international law and crimes against humanity. After a long history of temporary courts established to handle specific events, like the Nuremberg trials in 1945 – 46 and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in 1993, the statute established a venue in The Hague to try individuals who would otherwise stand outside a national jurisdiction.

The Rome Statute was ratified by the U.S. in 1998 by President Bill Clinton. It was “unsigned” by President George W. Bush in 2002 because his advisers, which included Bolton, believed the court assumed an authority that threatened U.S. sovereignty. The Bush Administration anticipated the situation that the U.S. faces right now, namely that citizens involved in actions performed under the direction of the U.S. military could not only be called before an international judiciary but could be found guilty of international laws purported to transcend the boundaries of the U.S. legal system. In a statement made on September 10th, Bolton affirmed the Bush Administration’s stance saying “the I.C.C. was created as a free-wheeling global organization claiming jurisdiction over individuals without their consent.” [1] Bolton adamantly opposes the authority of the I.C.C. to investigate the U.S. and said, “[the U.S.] will not cooperate with the I.C.C. We will provide no assistance to the I.C.C. We will not join the I.C.C.”

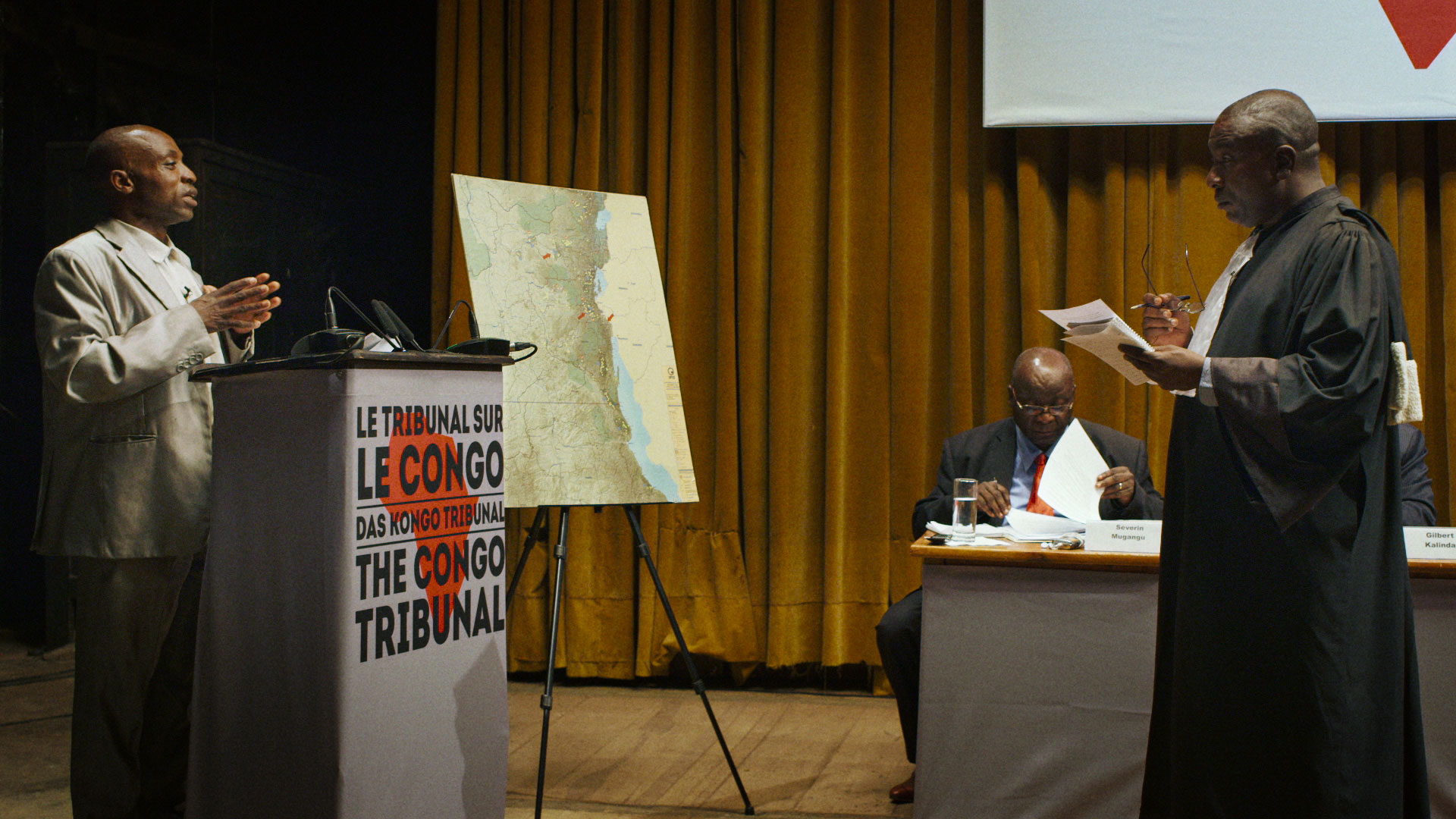

One wouldn’t expect the opinions of a decidedly conservative statesman like Bolton to be shared by a left leaning, Swiss artist like Milo Rau, and yet Rau’s work “Congo Tribunal” provides a similar critique of the I.C.C. In 2015, Rau began work on “Congo Tribunal,” a performance and film work that created a temporary criminal tribunal to investigate war crimes that took place in Rwanda and Congo during the 1990s. Rau agrees with Bolton’s assessment that the I.C.C. lacks the legitimate authority to enforce its findings. But while Bolton claims that the I.C.C. cannot usurp the power of the U.S. judiciary, Rau claims the I.C.C. is ineffective because it does not.

“Congo Tribunal” takes place in Bukavu / Eastern Congo, where an investigation of crimes against humanity takes place, and Berlin, where the findings are adjudicated. In bringing Congolese war criminals to trial, Rau brings the I.C.C. to a kind of trial as well. He claims that, because it has been traditionally supported by major global institutions like the U.S., E.U., World Bank, United Nations, and others, the I.C.C. is selective in who it prosecutes, oftentimes neglecting to hear cases that would involve these entities.

Others have criticized the I.C.C. for similar reasons. The Russell Tribunal in 1967, which “Congo Tribunal” was modeled on, brought charges against the U.S. for crimes against humanity during the Vietnam conflict. Though the tribunal found the U.S. guilty, the verdict had little effect.

If the I.C.C. chooses to move forward with its inquiry into U.S. actions in Afghanistan, critics like Rau would be proven wrong. However, an agreement between both sides of the political divide points to the court’s untenable position and casts serious doubts on its future viability.

If the I.C.C. lacks legitimacy in the ways that Bolton and Rau claim, how can we hold people accountable for crimes like genocide? This issue is highlighted in Chris Weitz’s recent movie “Operation Finale” where the proper venue for Nazi lieutenant colonel Adolf Eichmann’s trial is questioned. Should Eichmann be tried in an international court, like Nuremburg, or did his trial provide an opportunity to enact the legitimacy of the newly established state of Israel?

Eichmann’s trial, ultimately held in Jerusalem, was aired live over both television and radio and it was the first time that the public heard victims testify about the atrocities of the Holocaust. Though Eichmann’s trial was criticized by political theorists like Hannah Arendt because it sometimes neglected legal issues, it provides an example of the urgent need for public forums that discuss crimes targeted toward vulnerable people. Further, it demonstrates how the international community grapples with effectively addressing crimes that assault liberalism itself.

But is the I.C.C., as a specific entity, worth fighting for? Recent elections demonstrate that the idea of international citizenship is waning in favor of nationalist and populist sentiments found in countries like the U.S., U.K., Austria, Italy and others. Does this not demonstrate an ever-increasing need for an international judicial body to work in conjunction with the United Nations, one that has the capacity to enforce a ruling against a person who assists in the systemic violence against others?

As judges and lawyers in The Hague continue with their work, shifts in global politics have the potential to dismiss the I.C.C. altogether, leaving people at the mercy of governments whose actions see no consequence. Given that the stability of many institutions like the EU is questionable, the I.C.C. is probably not the highest priority for the international community. But it should be.

As the U.S. tries to position Russia as part of the G7, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea as a violation of international law now seems to be more of matter of an opinion than fact. Wouldn’t an international judicial body and its findings be helpful in determining to what level of involvement a country like Russia should play at the UN?

While the authority of the I.C.C. is questioned by politicians and artists alike, the need for some kind of international body to hold countries accountable for their actions is certainly not.

Image: Congo Tribunal http://www.artefact-festival.be/en/program/congo-tribunal-2015-17 © Milo Rau The Congo Tribunal, 2015-… Photo/ Fruitmarket _ Thomas Schneider 2017

[1] https://www.theepochtimes.com/speech-transcript-john-bolton-on-u-s-policy-toward-the-international-criminal-court_2656808.html

Leave A Comment