by Victor Wallis

October 2016

Is there a US Left? More specifically, is there a popular movement for socialism in the United States? And what chance does such a movement have for affecting national policy any time soon?

There have been several promising signs. The first was a national survey conducted in May 2012 which found that, among people under 30, there were slightly more who had a positive view of socialism than had a positive view of capitalism [1]. This is quite remarkable considering the endlessly negative evocations of socialism by politicians and the mass media. The second hopeful sign was the election to the Seattle City Council, in December 2013, of Kshama Sawant, representing a group called Socialist Alternative; she received an absolute majority against an incumbent Democrat [2]. Perhaps even more striking, she overcame a massively financed campaign against her to win reelection in 2015. Third, of course, is the popularity of the presidential campaign of “democratic socialist” Senator Bernie Sanders. Although Sanders’ conception of socialism corresponds to 1930s policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (a Democrat), his acceptance of the socialist label removes a stigma that had long been attached to it as a result of the ideological repression that has plagued the US Left through much of its history [3].

Underlying this new openness to socialism is a broader public awareness, especially since the economic collapse of 2008, that capitalism is incapable of satisfying the basic needs of the majority. This awareness is indirect but unambiguous. It is manifested in overwhelmingly hostile attitudes toward politicians and, more importantly, toward big corporations. These attitudes became sharply visible during the Occupy movement of 2011. More recent expressions have included nationwide demonstrations and strikes by low-wage workers against fast-food companies and against the mega-store Wal-Mart.

Still, there is an enormous gap between these developments and the emergence of a solid and coherent national political force with a capacity to grow. To understand this gap – and why it has been so persistent – we must return to a question that has been posed about the United States for more than a century: Why is the US so difficult for the Left? Deep structural factors are at work, and we need to take these into account before returning to the question of what can now be done.

The sheer size of the country is obviously a factor, along with the concomitant jurisdictional subdivisions. A comparison might be drawn with the political function of the European Union.

The EU is a ruling-class project, as was the 1787 Constitution of the United States. In both cases, the larger structure serves to override progressive agendas within any of its member-countries or states. The co-existence of two levels of government is very effective for this purpose, as it allows for the more conservative member-units, even if they are only a minority, to block changes which might otherwise be instituted in response to popular demand.

In the US in the 19th century, the institution of slavery was enforced by the federal government for many decades after a majority of the states had abolished it. Even after slavery was abolished nationally (as a result of the 1861-65 Civil War), a compromise was implemented whereby the federal government allowed the Southern states – in violation of the amended Constitution – to disenfranchise former slaves, who at that time comprised up to 60% (in Mississippi and South Carolina) of their respective populations. The Southern states were like the so-called “rotten boroughs” of the 19th-century British Parliament. Their “representatives” in Congress, however, would come to play a key role at the national level in enforcing anti-popular economic, social, and foreign-policy agendas.

This pattern was shaken up but not eliminated by the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. The Southern states to this day have disproportionate numbers of reactionary Congressmen and higher-than-average rates of poverty, incarceration, and executions. However, with the “war on drugs,” with the related policy of mass incarceration [4], and with the nationwide spread of laws and other practices impeding the right to vote, repressive measures traditionally associated with the South have spread to many parts of the country (especially urban areas, where there are high concentrations of African Americans and Latinos).

The laws in question are still enacted at the level of the particular states. There is no national guarantee of the right to vote; nor is there uniform legislation about what a new political party must do in order to get onto the ballot (i.e., to be officially recognized and offered to voters as a possible choice). A small number of states can thus prevent any new party from mounting an effective national campaign.

These structural obstacles to a Left party are reinforced by a number of historical and cultural factors. Most important is the way the present territory of the US was populated by its originally European settlers. The conquest of indigenous lands in the West involved military actions which often took on genocidal dimensions. The whole of what is now the Southwestern US (from Texas to Colorado to California) was conquered from Mexico. The pacification of all those regions was carried out – as was the post-civil War suppression of the black population in the South – with heavy reliance by local authorities upon the kind of vigilante enforcement depicted in classic “Western” movies. In the South, this took the shape of the Ku Klux Klan; in response to early working-class organizing in the North, it took the form of private armies like the Pinkertons.

All this is relevant to the particular ways in which repression has been applied against the Left. Because of the First Amendment to the US Constitution, with its guarantee (albeit qualified) of free-speech rights, restrictions on political advocacy have always had to be presented as embodiments of patriotism or religious values. This very trait, however, has also made the repression more sweeping than it might otherwise be, as “civil society” has become a willing instrument of government policy. The vigilante factor is thus implemented through partnerships between governmental and private enforcers (including organized crime), while huge private donations to political campaigns have combined with the mostly corporate-owned mass media to shape public opinion.

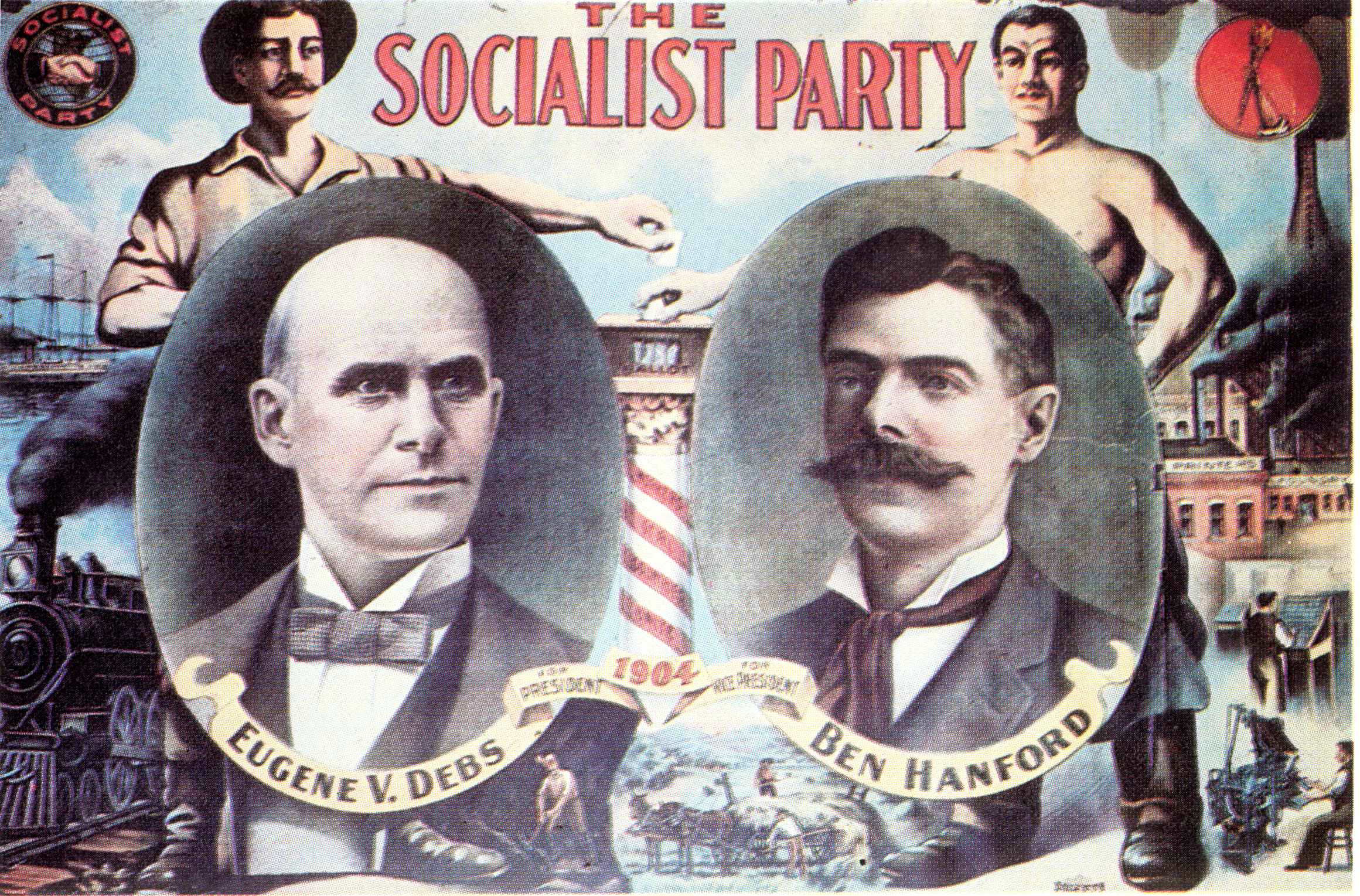

The first major wave of repression against socialists came during and immediately after World War I. Socialist presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs was imprisoned in 1918 under an expressly designed provision of that year’s Espionage Act. The wider campaign against the Left focused especially on immigrants (treating socialism as a “foreign” idea) and culminated in the 1927 execution of the Italian anarchist immigrants Sacco and Vanzetti on trumped-up murder charges.

A second wave of repression – perhaps the most severe ever within a “constitutional” regime – was carried out immediately after World War II. Although its ostensible target was the Communist party (against which the specter of foreign infiltration was again invoked), the rhetoric of “guilt by association” sought to discredit all progressive ideas, including in particular criticism of racial segregation and of US global military interventions. As in earlier repressive campaigns, the government operated in partnership with private entities, as business enterprises – sometimes prodded by the FBI – gladly fired employees suspected of having progressive opinions.

Where the earlier wave of repression had narrowed the popular base for the newly forming Communist party, the post-1945 stigmatization of the CP instilled among radicals of the 1960s a general apprehension about disciplined Left parties, and encouraged ultra-democratic aspirations instead. The resulting separation between democracy and discipline has not yet been overcome.

The political assassinations of the 1960s present many still-unanswered questions, but new insights are continuously emerging. Notable here is the account by journalist David Talbot, in his 2015 book The Devil’s Chessboard, of the plotting that culminated in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy (1963) and its official cover-up. The hand of the federal government has been most fully proven in the murders of Martin Luther King (1968) and of the influential young Black Panther leader Fred Hampton (1969). In the former case, as detailed in testimony at a civil trial, the murder also involved elements of organized crime (see William F. Pepper, An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King, and this presentation); in the latter, it was the direct work of the FBI’s COINTELPRO (Counterintelligence Program).

In terms of the Left, the significance of King is that he had become clearly radicalized during the last year of his life, and had the capacity to bring class-based and anti-war movements together with the movement for racial justice, offering inspired leadership to all of them. The Black Panthers, drawing directly on the legacy of Malcolm X (assassinated in 1965), represented a further radicalization, with deep roots in the urban ghettos and, in the case of Hampton in particular, a strong commitment to unify across racial lines.

With such promising beginnings systematically crushed, how can the Left regain the initiative and come to constitute an effective political force? What has it accomplished in the four decades since these events, and what new prospects may it find?

The last 40 years in the US have witnessed the almost uninterrupted escalation of neoliberal policies. Many of the social gains of the 1930s have been undone. Social mobility through higher education has been eroded as state funding has moved away from universities and toward the construction of prisons. All these developments help account for the new openness to radical alternatives. In addition, it is in this period that the ecological crisis has taken a central position in any popular agenda, providing compelling evidence of the need to ground economic activity in priorities other than profit [5].

There have also been some positive organizational developments. The steadiest advances have been in the sphere of alternative media. There are now numerous radical internet sites – some of which are listed below – whose combined audience is well over a million. This may not seem like much in a population of over 300 million, but its share of the politically active population is much higher. And the one million can be multiplied many times over when these media report an event of broad interest. It was through the alternative media (Wikileaks) that the sensational video of the helicopter-massacre in Baghdad (disclosed by Chelsea Manning) became known, and it was through the independent journalist Glenn Greenwald – writing for the UK Guardian but previously prominent in the US alternative media – that Edward Snowden was able to make public his revelations about the NSA’s (National Security Agency) mass surveillance [6].

The emergence of whistle-blowers like Manning and Snowden both reflects and contributes to the impact of an alternative media-culture, which in turn will provide – as it multiplies its reach –the necessary point of reference for the development of any serious Left political force.

Precursors to such a force have appeared sporadically during the recent period. One was the global and cross-sectoral alliance that blocked the 1999 conference of the World Trade Organization in Seattle; a similar alliance is now being mobilized to resist the Trans-Pacific Partnership (under which corporate-appointed international authorities would have the power, among other things, to override any national legislation that corporations might view as threatening to their profit-margins). A second precursor is the World Social Forum process, which has been mirrored within the US by the US Social Forum – gatherings of thousands of mainly low-income activists held in 2007, 2010, and 2015. A third precursor was the Occupy movement of 2011, which, despite its early dissolution, has continued to infuse political debate, crystallizing the opposition of the “99%” (working class and middle class) to the “1%” (capitalist class). Finally, there is the Black Lives Matter movement which emerged in 2014 and swelled rapidly in response to a succession of indisputably documented police killings of unarmed people of color [7].

As of October 2016, the latest harbinger of an independent Left force was indeed the Sanders presidential campaign. Although Sanders does not call for socialism (i.e., the expropriation of capital), he accepts the label of socialist. His candidacy therefore broadened the debate that can now take place. The concept of socialism is no longer out of bounds. It has been brought into the mainstream, especially among younger people, who may come to echo the refrain of the satirical song from 2012 by David Rovics, about Republican denunciations of Obama as a socialist: “If only it were true!”

Sanders himself continues to be constrained by the commitment he has made to the Democrats, expressed – even before he endorsed Clinton – in his failure to distance himself from the so-called “global war on terror” (a war that in fact provokes terrorist attacks). This unchallenged military agenda dictates – and is fed by – an entire culture of domination. A movement that fails to challenge this culture will be unable to question the enormous US arms budget or the racism and xenophobia on which it depends for mass acceptance and implementation.

The “billionaire class” that Sanders speaks of needs political leaders who, like him, give the downtrodden the feeling that they have not been forgotten, but it does not want a movement that will actually strip it of its power. Sanders’ rhetoric certainly makes the capitalist class uneasy, as reflected in the corporate media’s practice of giving his mass rallies as little coverage as possible [8] and in the relentless maneuvers by the Democratic leadership, during the Primaries (as revealed in the Wikileaks disclosures), to marginalize his campaign in whatever ways they could. These efforts persisted despite Sanders’ acceptance of the US global role (on which he criticizes particular policies but not the underlying assumptions [9].

Sanders did not mount a serious challenge to the mechanisms that were used to defeat him. Since capitulating to Clinton, he has energetically campaigned for her. He stresses the urgency of defeating Trump, which is ironic considering his much greater success than Clinton in appealing to the white working-class constituency to which Trump must look for mass support [10]. Sanders’ post-Convention organization, called “Our Revolution,” operates solely on behalf of candidates who are Democrats, and who therefore accept the policy-parameters that have shaped the status quo against which so many – especially among the younger generation – are now rebelling.

The challenge for the Left is to go further. This will mean fusing the existing movements for social justice – and climate justice – into a cohesive, working-class-based political force, while making clear that this cannot be done under the leadership of a party that fails to repudiate the current global role of US capital.

It is impossible to foresee what events might precipitate the needed “quantum leap” in political organizing. But, as the great historian Howard Zinn often reminded us, we have to build for that moment even though we can’t see it coming.

This text is revised and updated from an article originally written for and posted by the Norwegian website radikalportal.no (in February 2014). It was then posted in English at spectrezine.org, a website with a primarily European audience and at whowhatwhy.org, a site for investigative journalism.

For more information about the author, visit www.victorwallis.com

Important books:

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (1980, 2003) – a classic, translated into many languages.

William Blum, Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II (2003).

David Talbot, The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government (2015).

John Nichols, The “S” Word: A Short History of an American Tradition … Socialism (2011).

IMAGINE Living in a Socialist USA (2014) – a collection of 31 essays by socialist intellectuals and activists, edited by Frances Goldin, Debby Smith, and Michael Steven Smith.

Recommended websites:

Commentary: http://www.commondreams.org/ , http://www.counterpunch.org/ , http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/ , http://www.zcommunications.org/znet , http://www.truth-out.org/

Daily news and interviews: http://www.democracynow.org/ , http://therealnews.com/t2/

Activism: http://rootsaction.org/

This is the best written and most informative summary of social democracy in America, the forces that obstruct it, and the prospects for egalitarian justice, that I ever read. It is so lucid, so succinct, and so historically informative that it deserves a very wide audience indeed. Thank you for writing it, and thank you Political Animal for publishing it. I will share it with all my friends, and I’ll encourage them to share it as well.